Concept of duality

Duality can be considered as a weak form of symmetry. According to Wikipedia, in mathematics, a duality translates concepts, theorems or mathematical structures into other concepts, theorems or structures in a one-to-one fashion, often (but not always) by means of an involution operation: if the dual of A is B, then the dual of B is A, i.e. if the involution is represented as \(f\), we have \(f(f(A)) = A\).

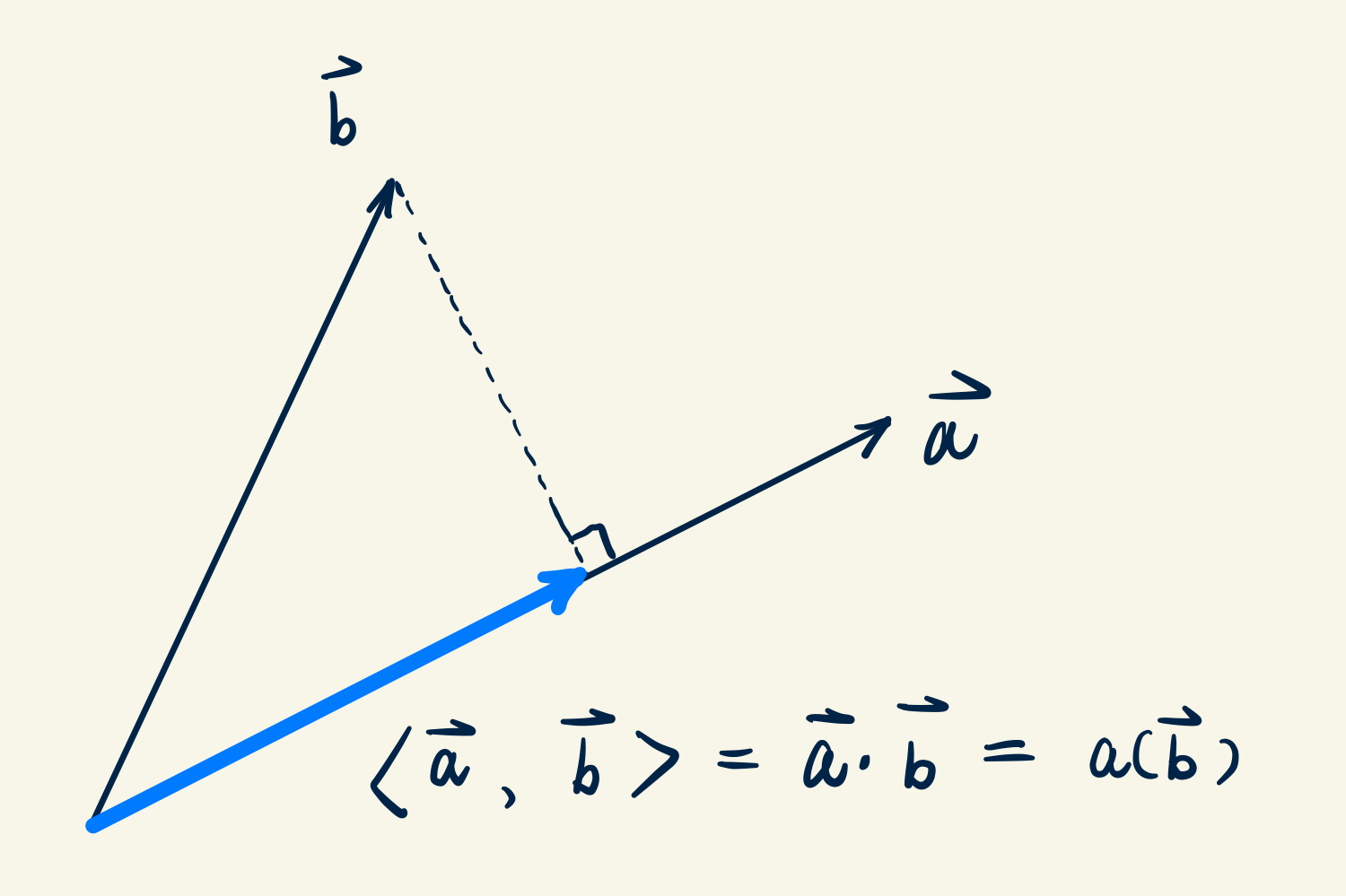

Taking the familiar inner product in linear algebra as an example (see Figure 1). The two vectors \(a\) and \(b\) have equal status, both of which are vectors in \(\mathbb {R}^n\). The meaning of inner product \(\left \langle a,b \right \rangle \) or \(a\cdot b\) is projecting \(b\) to \(a\). From the view of measurement, \(a\) is the measurement device and \(b\) is the object to be measured. For example, \(a\) can be imagined as an electric field meter, \(b\) is the electric field. When the meter is aligned with the electric field line, it registers maximum value. With this understanding, even though both \(a\) and \(b\) are vectors in \(\mathbb {R}^n\), we have a feeling that they have something different. If we adopt a matrix form to represent their inner product , \(a\) is a row vector, i.e. an \(1 \times n\) matrix, and \(b\) is a column vector, i.e. \(n\times 1\) matrix. Such a formal difference implies they are different types of vectors and the concept of duality is embodied in the correspondence between row and column.

Adopting the functional analysis point of view, \(\left \langle a,b \right \rangle \) or \(a\cdot b\) can be written as \(a(b)\). Now \(b\) is an element in the space \(X\) and \(a: X \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) is a linear functional or operator in the dual space \(X'\). In essence, \(a\) and \(b\) have different status and they are dual to each other.

In computer programming, \(a\) can be considered as a function or more generally a function object, while \(b\) is the data or operand to be manipulated.

In differential geometry, the core concepts of tangent space and cotangent space are dual to each other. Let \(M^n\) be an \(n\)-dimensional manifold which contains the point \(p\). \(M_p^n\) is the tangent space at \(p\). The dual space of \(M_p^n\) is the called the cotangent space at \(p\), which is written as \(M_p^{n*}\). A linear operator \(\alpha : M_p^n \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) in the cotangent space \(M_p^{n*}\) is called a cotangent vector or covariant vector or covector or 1-form. Applying this 1-form \(\alpha \) to a tangent vector \(b\), we obtain a scalar value. Due to Riesz representation theorem 1, there exists a unique tangent vector \(a\) such that \(\alpha (b) = \left \langle a, b \right \rangle \). This means the behavior of \(\alpha \) is governed by the inner product with respect to \(a\).

Theorem 1 (Riesz representation theorem) Let \(X\) be a Hilbert space and \(f\) be a bounded linear functional on \(X\), i.e. \(f \in X'\). There exists a unique vector \(a\) in \(X\), such that for all \(b\) in \(X\), \(f(b) = \left \langle a, b \right \rangle \) and \(\norm {f} = \norm {a}\).

In quantum mechanics, \(\langle \varphi |\) is in the dual space and \(|\psi \rangle \) is in the original space.

In FEM or BEM, the mass matrix \(\mathcal {M}\) involves the projection of a basis function \(\varphi _j\) in the ansatz or trial space to a basis function \(\psi _i\) in the test space \begin{equation} \mathcal {M}_{ij} = \int _\Omega \psi _i(x) \varphi _j(x) dx. \end{equation} \(\psi _i\) and \(\varphi _j\) can also be considered dual to each other.

Related: Measurement and duality

Backlinks: 《Integration of differential forms and its relationship with classical calculus》